What is the Silver Layer?

The silver layer in a medallion architecture is the bridge between raw, messy data and the polished, business-ready gold layer. Think of silver as the data team’s source of truth – the foundation for building data products – while gold is the source of truth for the business.

Silver holds the building blocks: cleansed, standardised data that’s ready for modelling or applying new business logic. It’s also normalised, meaning the data is organised into related tables to reduce duplication and improve consistency. Between bronze and silver, you handle the basics – deduplication, fixing formats, dealing with nulls – so you never have to wrestle with the original chaos again.

Doing these transformations once, in silver, means every project starts from the same clean slate. It speeds things up, avoids rework, and enforces governance. When everyone uses silver, you can trust the data – no more “my version vs your version” or “how did you get these figures” or – my personal favourite – “it doesn’t feel right”. If you get those rules agreed, then the silver layer is trusted, endorsed and consistent (data governance is a whole other can of worms we can get into another time!).

You can go back to the case study here.

Modularisation

Modularisation isn’t just for code. It applies to transformation steps as well. I split transformations into separate notebooks, each handling a single (or a couple of dependent) task/s. This makes them reusable and easier to maintain. If only one table needs refreshing, that notebook can run on its own without triggering the entire workflow.

Once the steps are modular, I use a pipeline or an orchestration notebook to run them in the correct order. This approach keeps the process clean, avoids tangled workflows, and makes debugging far less painful.

Transforming Bronze to Silver for FPL

Remember in the bronze layer we have, for each season, 2 main datasets. ‘players_raw’ and ‘players_gameweek_stats’. From these 2 datasets we need to untangle all of the elements into usable tables – namely fixtures, players, teams and player_gameweek_stats. To do this we have used PySpark notebooks to extract the required data, transformed as below, then overwrite/merge to a table in the silver layer.

We also have 2 methods of getting the data – from the historic CSV schemas and the new API that we will use for the current and future seasons. Each data source required slightly different code to manipulate and combine them as the schemas are different. As always, the code can be found here, and this post is merely an explanation of thought process.

For each season, each player and team have an ID relative to that season, and then overarching ‘code’ (we will call them ‘key’) that map each player/team across seasons.

Fixtures

The first place we start is getting the list of fixtures for each team and season. We do this by using “id” (player_id) and “team_code” from the players_raw tables, along with the following columns from the player_gameweek_stats tables: “element” (player_id), “round” (gameweek number 1-38), “fixture” (fixture id), “opponent_team”, “was_home”, “team_a_score”, team_h_score”, “kickoff_time”.

We group, join and filter these datasets until we get a fixtures dataset which contains the home and away team key, the score (where applicable), kick off time, as well as a few keys – we will build a unique key for all of these tables e.g. fixture_key = season (202526) + fixture_id to 3 digits (034) that we are able to join on.

Players

We manipulate the 2 datasets in similar ways – by extracting the relevant columns and merging, grouping and joining to get a dataset that contains all the data we need about a player. This is data such as player name, position, team, as well as FPL stats such as initial and final value (how much the player costs to be in your team).

In silver.players, we don’t just have 1 row per player. It is designed with player_id (season-relevant ID) and a player_key (the player_code assigned by FPL), so we have a row per player per season (in case they move teams between seasons). Using keys is better than just the ID, as now we can link a player’s data across seasons.

But wait! This is still not enough. A player may play for multiple teams during a season – so having 1 row per season per player_key is not enough. We need to add a ‘first_fixture_key’ and ‘last_fixture_key’ to understand when this row is valid (think Type 2 slowly changing dimensions). There are some cases where a player plays for Team X in August for a game or 2, transfers to team Y before the transfer window shuts and plays for them until the rest of the season. There are even cases where the player is transferred again or recalled before the end of the season – meaning their ‘timeline’ for the season involves playing for 3 different clubs over ‘spells’.

So we need a player_spell_key which is season_key + player_key + which different spell that season the row refers to. This is now unique for the players table, albeit we won’t use it often to get player stats – the stats can’t be against the same player for 2 different teams in the same fixture (you’d hope!).

Teams

I’ll admit I cheated with this one. There is no clear ‘team’ data using these raw player datasets, just team IDs and the player data.

We extract all of the unique team IDs per season and a random player name from each, as well as the team_code which links the same team across seasons. We then export to Excel and manually fill in a CSV to capture the necessary data using ball knowledge and a bit of Google to work out which team ID and key is being referred to. We then import the CSV into the raw layer and ingest straight to silver.

Now we have silver.teams which has the team_key (consistent across seasons), the team_id per season, as well as whether the team was promoted or relegated in that season.

Sometimes a spreadsheet is the best way!

Player Gameweek Stats

The gameweek stats are pretty straightforward, we have most of them already. We combine all the schemas and set data formats, as well as add a couple of flags “exp_points_available” and “def_con_available” to indicate whether some stats are present (older seasons don’t have expected goals, for example).

We add identifier keys such as fixture_key, player_key, season_key to be able to join to other tables. The unique key in this table is ‘polayer_fixture_key’, which is player_key + fixture_key. We can identify who the opponent was and the final score using the fixtures table. Finally, using the match statistics we can work out the FPL point scoring for each player – goal points based on position, etc. – and then save to silver.player_gameweek_stats.

Seasons, Gameweeks & Positions

The main tables are complete, but for completeness we want to add reference tables to be able to join on and give us richer data about gameweeks (1-38 and the first and last kick-off times), seasons and the positions used in FPL.

We do this by manipulating the fixtures table and then ‘hard-coding’ the positions into a dataframe and saving to a table.

Summary

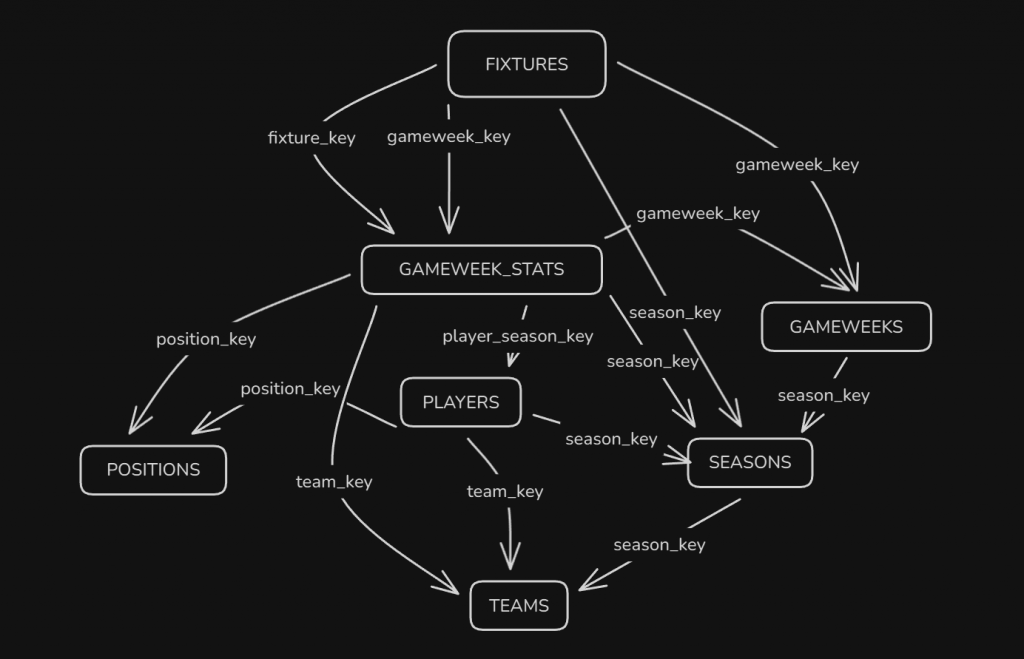

We now have a silver layer that we can build from! An extremely basic schema diagram is above, which can be created using quite a handy script. These normalised tables can be used for feature engineering and machine learning, or straight into the gold layer and reporting!

BW

Looking good Ben.